Sometimes it pays to procrastinate. It took Alexander Chee fifteen years to complete his second novel, The Queen of the Night, and about seven years in, during a particularly bad case of writer’s block, he spoke to his agent, Jin Auh at the Wylie Agency, about putting together a collection of essays instead. “It was one of many moments where I was like, ‘Is there anything I can do to get out of writing this novel?’” Chee says. While, thankfully, he persevered and completed The Queen of the Night, which was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in 2016 to much critical acclaim, Chee continued to gather his previously published and discarded essays during the slow periods in his fiction writing. “It was this weird shadow creature that grew in the process of writing both my first and second novels,” he says, “almost like a back passageway to them.”

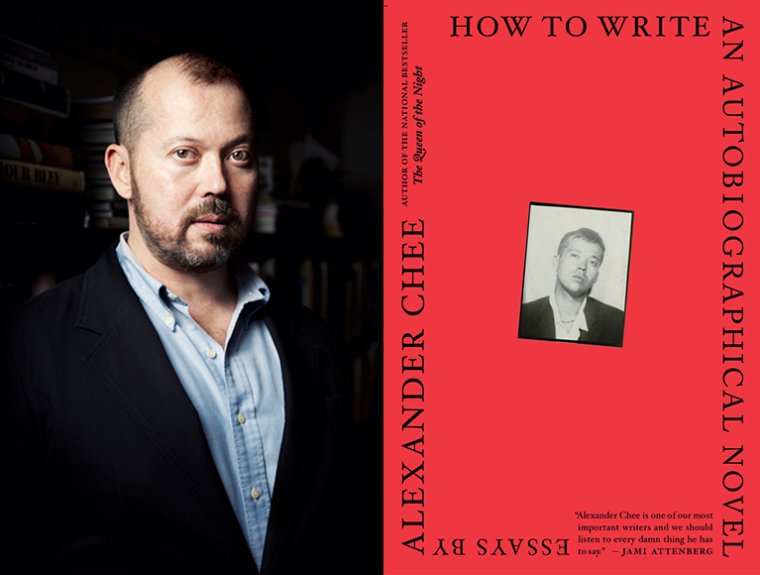

Novelist Alexander Chee, author of the new essay collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, out this month from Mariner Books. (Credit: M. Sharkey)

Chee has made his name as a fiction writer. His first novel, Edinburgh (Picador, 2001), which tells the story of a Korean American boy who is forced to deal with the devastating effects of being molested by his choir teacher as a young teen, won the $50,000 Whiting Award. The Queen of the Night, a sweeping period novel in which an orphan moves from America to Europe to become one of Paris’s most famous opera divas, was a national best-seller and a New York Times Editors’ Choice. But for as long as he has been writing fiction, Chee—who is an associate professor of English and creative writing at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire—has also been quietly publishing essays in venerable journals and magazines such as n+1, Guernica, and Out. And with the release of his first essay collection, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, out this month from Mariner Books, his “shadow creature” has stepped fully into the light.

The collection, which includes both previously published essays and new works, covers a wide range of subjects, all explored through the lens of Chee’s own life—from performing in drag, to a rose garden he grew outside his Brooklyn apartment, to a stint as a caterer for conservative socialites William F. and Pat Buckley. But as disparate as some of the topics are, they all circle back to one central question: How do we live and write truthfully? For Chee, a Korean American gay man growing up in a small white town in Maine, who came out at the height of the AIDS epidemic, the answer to that question has been fraught. But in his essays Chee explores the ways in which, despite tremendous external resistance, he forged a more consistent, authentic self both in life and on the page. The book is part memoir, part writer’s guide: While Chee mines the territory of his own life, he also offers useful advice about how other writers might do the same. In his essay “100 Things About Writing a Novel,” for instance, he offers this sage bit of wisdom for fiction writers: “The family of the novelist often fears they are in the novel, which is in fact a novel they have each written on their own, projected over it.” Many of the essays also include writing advice from Chee’s mentors, including his beloved undergraduate teacher Annie Dillard, and Deborah Eisenberg, his first professor at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop. In some ways, the book is far less a back passageway than it is a map, leading the reader to a deeper connection with both herself and the risky, rewarding act of creation.

I spoke with Chee about his new book, a lively conversation during which we discussed how to keep working during bouts of self-doubt, methods for successfully spying on yourself, and whether dancers do in fact make the best writers.

How do essays function for you in relation to fiction?

I studied with Annie Dillard, and that set the tone for how I came to think about essays and their possibilities. Annie told us, and I didn’t realize how radical it was for her to say this, that you make more money from nonfiction. If you become good at essays you can sell them while you’re working on your fiction. If you’re trying to start a writing career, you can use a finished essay as both a writing sample and an introduction to an editor, and while that editor may not like what you’ve written specifically, it might create a relationship that will yield work in the future. Everyone else [who taught in my writing programs] had a kind of, “I don’t talk about business in class” mode, which, I think, is unfortunately quite common in creative writing. And I say unfortunately because the truth is that one of the ways you democratize literature is by teaching people how to make some money so that they can get by.

Yes, and how to talk honestly with each other about the money they are making.

Yes, and how to stand up for the money that they are making. Annie encouraged us back then to have all of those conversations, taught us the format for submitting work, taught us to use the Best American anthologies as a guide to the places we should be submitting work to, taught us even to double check the addresses in the mastheads because some of them used codes to sort out who was only combing Best American anthologies for their address. Annie Dillard is no joke.

You’ve said before that we are living in a more “essay friendly” time. Can you say more about that?

The irony of the Internet, which was supposed to rob us of our attention span and be the death of journalism, is that it has actually promoted a new passion for longform nonfiction. It’s also given us more opportunities to find and discover poets, who are a big part of the movement towards essays as well, since they are doing work that is increasingly hybrid. In general, the best thing I can say about social media and the Internet is that it has allowed a lot of people to bypass the gatekeepers, such that I don’t know if there’s a real gate any more.

You say in the book, and you’ve mentioned this on social media before, that readers often want to know what’s “true” in fiction. What is your relationship to “the truth” in writing, and does it vary between mediums?

I think fiction is the thing you invent to fit the shape of what you learned and nonfiction is the thing you invent to fit the shape of what you found or maybe even what you can’t run away from. One thing that I noticed during the editing process of this book was how often it felt like I was dying. [Laughs.] It was just soul crushingly depressing and difficult work and it took so much longer than I thought it would. I had this kind of idea of, “Oh, I’ve published a lot of these essays before and this won’t take a lot of time.” Boy was that naive. It was shocking how naive that was. I think that’s because when you do it right, and this goes back to what Annie used to say, it’s a moral confrontation the writer has with the truth of their experience. That is no joke, and that is not a thing you can just rush through. In literary fiction I think you’re watching someone else in a landscape, wondering if they’re ever going to figure out who they are. In nonfiction of this kind, what you’re doing for your reader is riddling through the ways you lie to yourself and others and trying to get at what you actually believe.

Yeah, it’s horrible.

And that’s why you feel like you’re dying, because the part of you that your ego has held is saying, This is me, while the essay is saying, Well, it’s nice that you think that, but…

You’re actually over here, in this big pile of shit.

Right. Mary McCarthy wrote this essay collection Memories of a Catholic Girlhood. In between each of the essays she has a few pages about what she made up, what she lied about, what she didn’t mention, and she just calls herself on all of it. And it was this interesting early lesson when I read it about how much you have to be on your guard about yourself.

What were some of the lies you had to let go of in writing this book?

I engaged in a kind of forensics of the self. It was something that, again, Annie had taught. An early exercise of hers was called something like, So you think you know your hometown? And she asked us: “Do you know the major populations in your hometown, do you know the major industries, do you know the flora and fauna of the different seasons, do you know the historical events that shaped the founding of the town? How much do you know and how much are you actually just around for?” I continued to take that approach with myself. I reread my journals and all my e-mails. I look at my social media “likes” history to find out what I’m actually paying attention to, and my browser history for the things I won’t even allow myself to “like” publicly. I act like a spy on myself, like someone who doesn’t love me and is just going to report on me. It’s a trust-but-verify relationship to the self.

In the book you write about how Annie Dillard said to you, “Sometimes you can write amazing sentences and sometimes it’s amazing you can write a sentence.” Has getting that kind of feedback helped with this honest relationship to the self?

[Laughs.] I had a high school English teacher who said to me, “What I love about you is, I can knock your head off, hand it to you, and you just put it back on, straighten it and keep going.” And I think my ability to just hear people say those things and figure myself out in relationship to what they’ve said has made a big difference. As I’ve learned from a long teaching career, not everyone is built that way, and I’m very glad [my English teacher] identified that early on. He once took a paper of mine and read it aloud without telling me he was going to read it and at the end he just said, “This is an example of what not to do with metaphors.” I could have been upset but I thought, “Okay,” because I respected him and I knew I was showing off what I could do with words in a way that was overblown.

In this collection, was there a hardest essay or an easiest essay, or were they all hard and easy in different ways?

That’s a good question. They all presented different challenges. Some of them were written in the nineties and abandoned and then revisited and abandoned again. “The Guardians” and “Autobiography of My Novel” were, for a long time, one essay and then I turned them into two essays. I started [the original piece] when I was about to finish my first novel, Edinburgh, and it was originally going to be one of those essays you publish in support of your novel—which has become this weird tradition that my essayist friends really hate because they’re like, “Who are these fiction writers showing up, thinking they can write an essay and flooding the market with low quality pablum?” And it’s true that writing a novel, writing a short story, and writing an essay are distinct skills.

My essay “Girl” was one that I actually workshopped initially at Iowa. I worked on it for a few years before deciding it was possibly juvenilia and set it aside. And then every few years I would pick it up and think, “This is pretty good, I should do something with it,” and I never would. And finally Guernica reached out to me and said, “Do you have anything about gender?” And I sent them that essay. I think I was like a lot of my students. I thought success in grad school or in a writing class was a kind of low bar, that it didn’t mean anything about success in the world, which to my mind had to be so much harder, and so I talked myself out of submitting a lot of work that I could have submitted earlier and who knows what would have happened. I think in this culture there’s such a value placed on hard work that your inherent talent can seem like something silly. So I ignored it for a while.

In “After Peter,” you talk about your involvement in the activist group Act Up and growing up in San Francisco during the AIDS epidemic. I’m wondering, how did coming of age in that time affect your sense of your body and sex and intimacy?

I think intimacy is always fraught but it was differently fraught because of the AIDS epidemic. At that time, in the nineties, I was also just starting to experience the return of memories I discuss [in the essay] about being abused, and so my body was a kind of unfamiliar territory. Dustin, my husband, has memories of being in Hell’s Kitchen during the same time and seeing guys going up to the rooftops to jack off and watching each other at a “safe distance.” He said it was like jerking off in silence with the biggest condom of all, this gap of space between buildings.

Do you feel like writing has changed your relationship to your body?

I think, in general, I often ignore my body because of writing, to my own detriment. So I’m trying right now to reinhabit my body. But I have noticed that students of mine who have a background in dance are often quite talented at writing as well. There’s some way of thinking about how the body can be articulate that translates into how you tell stories on the page. I don’t know if it goes the other way. I’d love it if it did. The body is the instrument for the essayist in particular. It’s the instrument by which the events are recorded; it’s the instrument on which the events are replayed. It’s a very complicated, interdimensional relationship we have with our bodies when we’re nonfiction writers.

You’ve written about your family in different ways in this collection. The line of what writers will share and won’t share about family is always different and I’m wondering where that line is for you.

One thing I know is true for Asian and Asian American families is there’s a lot of intergenerational silence, so my mom [who is white] is the source of a lot of the stories I have about my dad’s family, which she learned when we were in Korea, because she doesn’t have any of those social taboos. There is also the silence of my father’s death, which is certainly a profound one for me—I’ve spent a lot of time in relationship to my memories of him and my imagination of him. One of the first essays I wrote, which I almost put in this collection but held back, is a confrontation with the memory I have of my father and what would happen if I told him I was gay, because he died before I could come out. That early experience of having to think through that and write what his reaction would be, which also meant writing about my mother and my sister, got my family used to the idea that I was going to write this book. And my mom read it and offered some insights into what she felt I’d gotten wrong about her, but she said, “It’s your truth.”

“Girl” was such a powerful example of all the ways you’re straddling different worlds: boy/girl, gay/straight, Korean/Korean American/white. Does writing feel like it creates bridges or synthesis, or is it just an observation of the gaps that are there?

I have come to view writing as a sort of prism. Early on, at a time when I was experiencing a crisis, I had a therapist who said, “You are different with different people because you are uncertain whether you can be whole with any of them, and the result is that you feel inauthentic with all of them and you may even feel inauthentic to them. So you need to pursue a complexity in the relationships you want to be your core relationships and that will help you feel more authentic to yourself.” That was the source of a profound breakthrough because what I was experiencing as depression was a kind of self-rejection predicated on my imagined sense of other people’s rejection.

At some point you have to make a choice about which story you are going to tell about yourself. Are you going to tell a story of you as a failure who never did the thing that you wanted to do—which is the story you essentially tell yourself, a kind of private theater of pain—or are you going to tell the story that you’re working on, a story that can actually reach other people and connect outward to the world? If you’re busy telling yourself that other story about your own failure, chances are you aren’t writing. You may think you are protecting yourself by keeping yourself from writing, but that’s really not protection at all. That’s just another story trying to talk you out of being yourself.

Listen to Alexander Chee read an excerpt from How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.

Amy Gall’s writing has appeared in Tin House, Vice, Glamour Magazine, Guernica, Brooklyn Magazine, and PANK, among others, and in the anthology Mapping Queer Spaces. Recycle, her book of collage and text coauthored with Sarah Gerard, is out now from Pacific Press. She is currently working on a collection of linked essays about sex, violence, and bodily return.