Writer, vocalist, and sound artist LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs is the author of TwERK (Belladonna, 2013), as well as the album Television. LaTasha has received scholarships, residencies, and fellowships from Cave Canem, Harvestworks Digital Media Arts Center, VCCA, The Laundromat Project, The Jerome Foundation, New York Foundation for the Arts, the Eben Demarest Trust, and Millay Colony. As an independent curator and artistic director, she has directed literary/music events at Lincoln Center Out of Doors, Symphony Space, Bam Café, The Schomburg Research Center for Black Culture, Dixon Place, El Museo del Barrio, The David Rubenstein Atrium. A native of Harlem, LaTasha and writer Greg Tate are the founders and editors of yoYO/SO4 Magazine.

Building the Architecture of My Lineage, Part 1:

I do not recall the entire conversation, only the moment when the poet Hoa Nguyen suggested to a class of writers that we figure out the "architecture of our lineage." Her talk had to do with her life as a writer and building community—a community that reflected one’s own personal influences and peers. One that reflected each of us as writers. She did not offer detailed instructions. There was no how-to-book on building community. But the phrase “the architecture of my lineage” left an imprint on me, and upon returning from graduate school to New York City, building community took on a number of manifestations in my life.

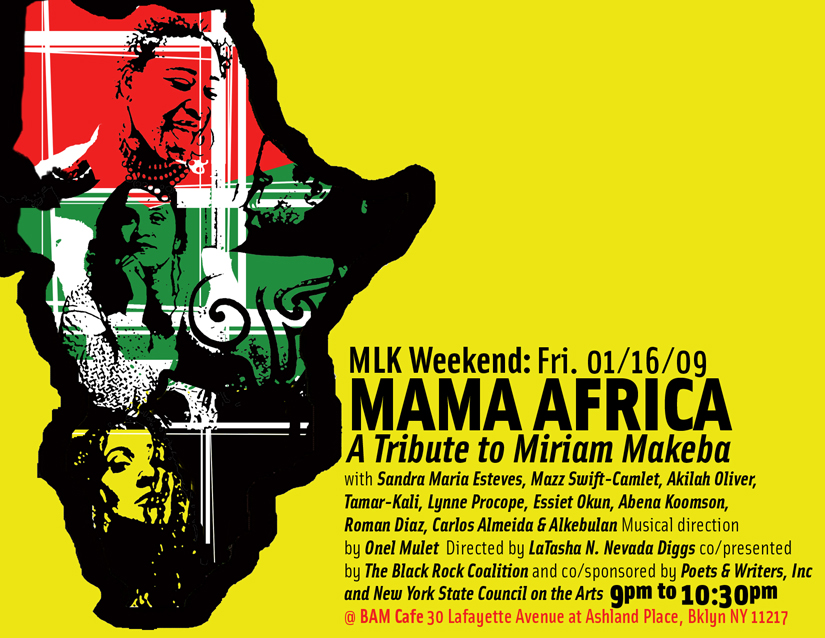

My creative work, for some twenty years, fluctuates between poetry and music with small moments in theatre and media. My decision to relocate to California was two-fold. I needed a break from New York. I needed to figure out if I was indeed a writer. Those two years away meant that my return to New York would require a type of resurgence. At the same time, my interests became less and less about my work. In fact, I thought little of it until the passing of Miriam Makeba on November 8, 2008. She was born the same month and year as my mother and despite obvious differences, I felt honoring her was to honor my mother’s generation. Miriam was definitely part of that lineage. So without much thought, I called Darrel McNeil, the associate producer of music programming at BAM Café Live and asked if I could assemble a tribute to her as a free concert. To my surprise, I got the ok.

What came next was a crash-course in project management. I had to write up a project description—something brief, something that would be handed over to other staff members. I needed to come up with a technical rider. If you languish over writing seventy-four-word artist statements, try your hand at concert proposals. The main focus of this event would take inspiration from a Makeba concert at the Salonger in Sweden in 1966. From this show, I proposed that selections from her catalogue be re-imagined and that the poets write new work for this occasion.

This tribute was to also reflect my artistic and cultural influences and admirations. It needed to represent the African Diaspora. So I invited poets Sandra Maria Esteves, Akliah Oliver and Lynne Procope. Having these three women poets meant having three generations of women who greatly informed my own work. I also invited vocalists Tamar-kali, Alkebulan X and Abena Koomsom (also a poet) who brought their artistic specialties from the Gullah Islands, Puerto Rico (via The Bronx) and Ghana. Lastly was the musical ensemble that consisted of Roman Diaz on percussion, Mazz Swift (also a featured vocalist) on violin, Essiet Okun on upright bass, and Carlos Almeida on guitar—all under the direction of Onel Mulet. Cuba, Trinidad, Ghana, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, St Louis, and the Gullah Islands were all here. I felt this represented just how far Miriam’s voice had reached.

I had produced a handful of music and poetry events in the 1990s, but this was different. More than ten years had passed. We needed rehearsal time. I needed a budget. BAM Café could only provide so much and a suggestion was made to have The Black Rock Coalition step in as a co-presenter. The BRC has had a long history with poets, and their very first concert at The Kitchen featured the late Sekou Sundiata. So it made sense. But even with the inclusion of BRC, my budget could not cover the even most modest of honorariums much less rehearsal hours. That is when the decision to apply for a Poets & Writers matching grant came into play. I suggested that the BRC apply on behalf of the poets, and the request was approved. And on the night of January 16, 2009, we celebrated the life and work of Miriam to a packed house of artists, non-artists from several generations and cultural backgrounds.

I did not foresee this impulse that would lead me to organize an event such as this. Now, life as an artist personally requires the ability to pull away from the front stage or podium and allow other artists feature their creative talents. For on those rare occasions when I am an ensemble member, I know how much the opportunity inspires my own creative growth. I returned to New York City wanting to worry little about my work and ended up learning the joys, struggles, rewards of being a young curator/producer.

For now, part of my mission to create musical/literary events that are both cross-generational and cross-cultural is a personal and constant investigation of what “building the architecture of my lineage” means.

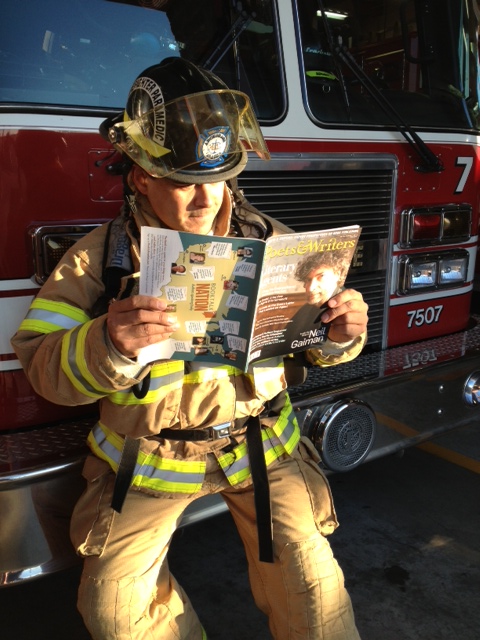

Top Photo: LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs. Credit: LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs. Middle Photo: Akilah Oliver. Credit LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs. Bottom Photo: Mama Africa Flyer.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. Additional support is provided by the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Trust, the Cowles Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Founded by Dzanc in 2011 and inspired by Lisbon poet Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the annual DISQUIET International Literary Program is a two-week retreat that brings together North American and Portuguese writers in the heart of Lisbon. The program offers

Founded by Dzanc in 2011 and inspired by Lisbon poet Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, the annual DISQUIET International Literary Program is a two-week retreat that brings together North American and Portuguese writers in the heart of Lisbon. The program offers

Poets may submit up to three poems of any length; prose writers may submit a short story or essay of up to 8,000 words. The entry fee is $20, which includes a copy of the Spring issue. Submissions will be accepted online via

Poets may submit up to three poems of any length; prose writers may submit a short story or essay of up to 8,000 words. The entry fee is $20, which includes a copy of the Spring issue. Submissions will be accepted online via