Poet Sueyeun Juliette Lee reports on her P&W–supported reading and workshop with the experimental Houston collaborative Antena. Lee is the author of Underground National (Factory School Press, 2010), That Gorgeous Feeling (Coconut Books, 2008), and Solar Maximum, forthcoming from Futurepoem Press. In addition to her writing, Lee publishes innovative work by multiethnic authors through Corollary Press. She also edits for The Margins, the web magazine of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and EOAGH: A Journal of the Arts.

Antena, made up of Jen Hofer and John Pluecker, is a language justice and experimentation collaborative, currently in residence at the University of Houston’s Blaffer Art Museum. In addition to curating an immense exhibition of book arts and small presses from the Americas (North, Central, and South) alongside text-based visual work by eleven artists from Latin America and the U.S., they also pulled together artists, small press publishers, and writers to convene this past February for a weekend of workshops and dialogues about community and art in a multi-national exchange. I was one of the invited artists.

In order to facilitate this cross-cultural exchange, Antena utilized real-time interpretation, which required all participants who weren't comfortable in both English and Spanish to wear headsets and radio receivers. Bilingual interpreters were present at each event and interpreted live for the participants by broadcasting on different radio channels. Though it was often challenging to listen through the headset, the experience underscored and manifested the obstacles we must wade through if we want to have a true encuentro, or encounter, with difference.

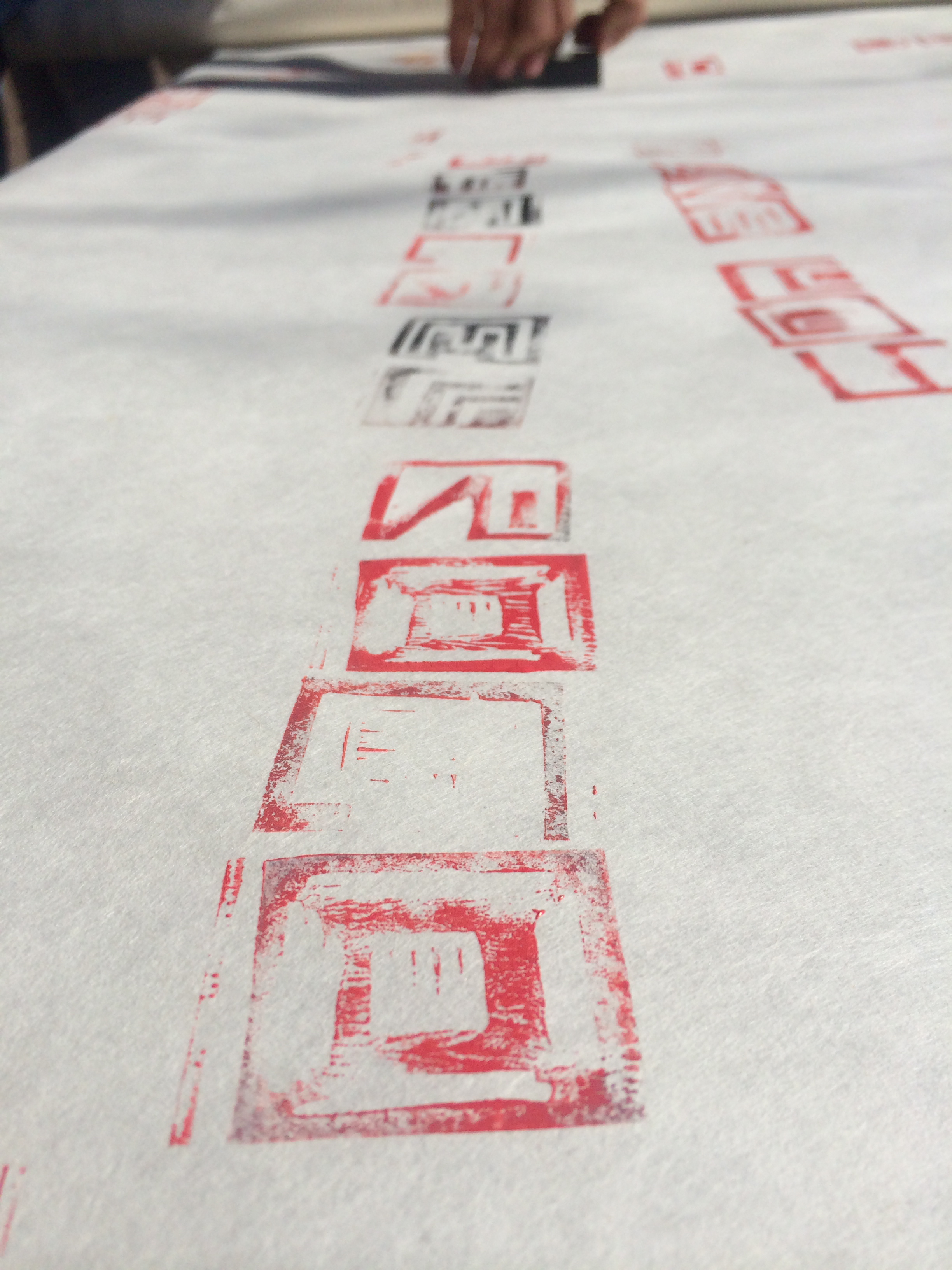

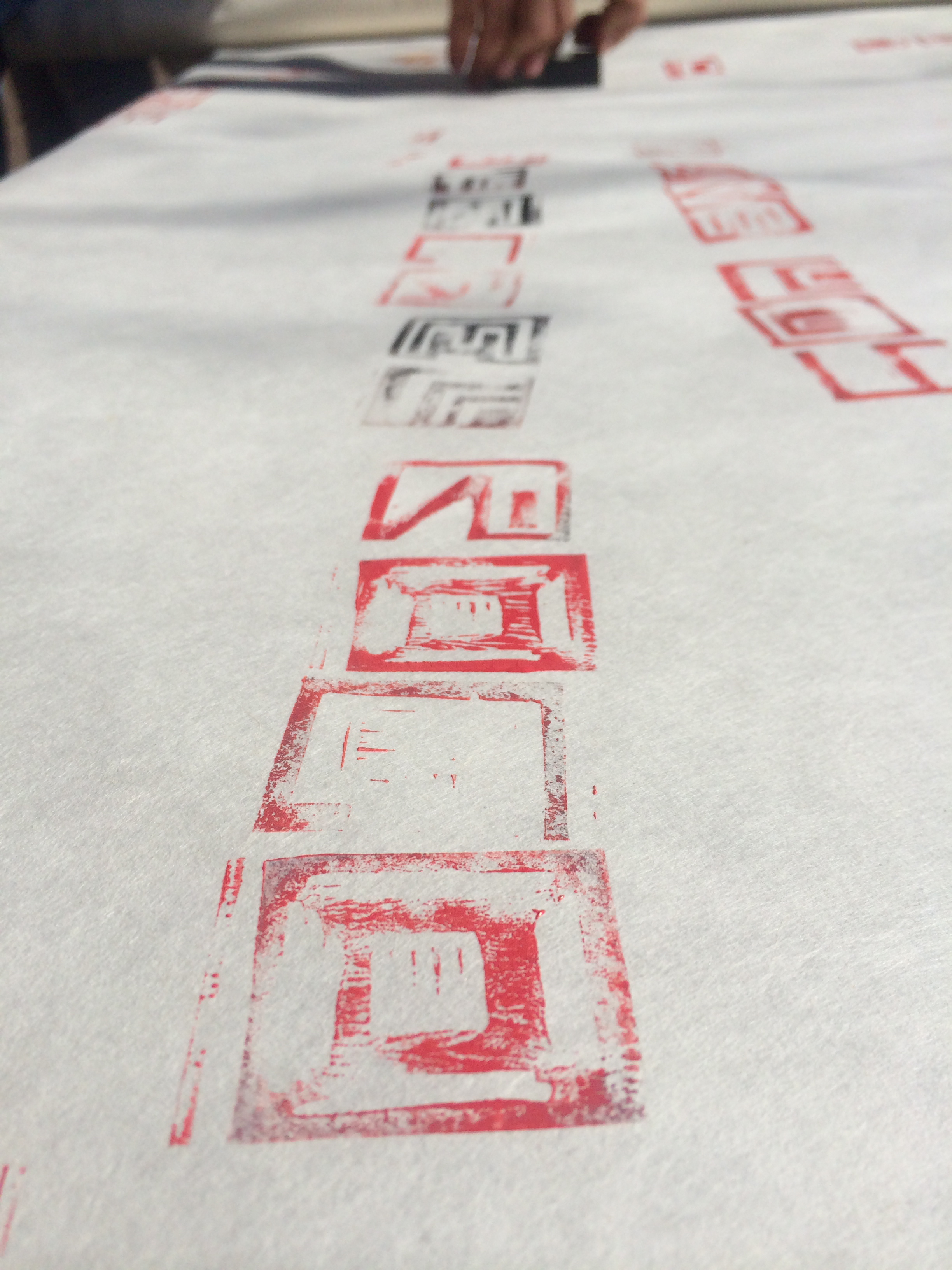

The workshops ranged from creating language-oriented artwork together, such as making a massive collective block print with Nuria Montiel of all of our favorite phrases, or participating in performance experiments led by Autumn Knight, who invited us to engage each other in playful new ways. The evenings were devoted to performances of all the featured artists’ work.

I was incredibly impressed by the audience’s diversity. There were of course many undergraduate students there, since we were located on the University of Houston’s campus, but Antena’s commitment to community and access was evident in the range of other workshop participants and attendees from all walks of life. One older woman approached me and told me she was not a “poetry type,” but was profoundly moved by all the things she had heard that night. She was clearly deeply affected. Isn’t that the greatest feat we can hope art will accomplish?

I was astonished by the cross-arts resonances that emerged between us. For example, I met Guatemalan visual artist and indigenous activist Benvenuto Chavajay, who asked me about the kite I had made for the exhibition. His country has an annual kite celebration, and we discussed the ways that kites impact national and cultural identities. Though I am a Korean American, raised outside Washington D.C. by immigrants, and Chavajay is of Mayan descent, we had very similar understandings about the kind of transformative work we wanted to accomplish through our art, and the way that we understand our relationship to our heritages and histories.

There are many moments from the Encuentro that I will never forget—especially watching Stalina Villarreal toss her “bouquet” of poems into the air and hearing Ayanna Jolivet McCloud’s skin as she rubbed the microphone across her body.

Top: Encuentro participants; credit: Pablo Gimenez Zapiola. Bottom: A collaborative block print; credit: Sueyeun Juliette Lee.

Support for Readings & Workshops events in Houston is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

Women poets may enter the To the Lighthouse Poetry Book Prize by submitting a manuscript of 48 to 96 pages (two-thirds of which must be unpublished); women fiction and nonfiction writers may enter the Clarissa Dalloway Book Prize by submitting a manuscript of 50,000 to 150,000 words. Novels, novellas, memoirs, biographies, young adult literature, and graphic novels are eligible. The entry fee for both prizes is $20; entrants may submit using the

Women poets may enter the To the Lighthouse Poetry Book Prize by submitting a manuscript of 48 to 96 pages (two-thirds of which must be unpublished); women fiction and nonfiction writers may enter the Clarissa Dalloway Book Prize by submitting a manuscript of 50,000 to 150,000 words. Novels, novellas, memoirs, biographies, young adult literature, and graphic novels are eligible. The entry fee for both prizes is $20; entrants may submit using the